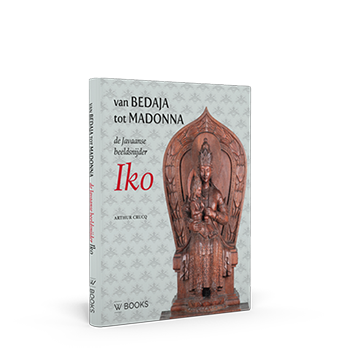

From Bedaja to Madonna: the Javanese Sculptor Iko

English summary of De Javaanse beeldsnijder Iko

Van bedaja tot Madonna, Dr. Arthur Crucq, 2024.

In Ganjuran, south of Yogyakarta, Middle-Java, an extraordinary Catholic church and an even more extraordinary Sacred Heart Chapel (Fig. 1) was erected on the site of Gondang Lipoero. Gondang Lipoero was a sugar plantation and factory in the 1920s owned by the Catholic brothers Josef (Jos) Ignaz Julius Marie Schmutzer (1882-1946) and Julius Robert Anton Marie Schmutzer (1884-1954). Together with their partners, Lucie Cornelie Amelie Schmutzer-Hendriksz (1896-1979) and Caroline Theresia Maria Schmutzer-van Rijckevorsel (1894-1990), they devoted themselves to a Catholic mission. They founded schools and hospitals on and near the company’s premises. With the hopes of also building a church and chapel there, the important question became: how would the designs take form and what statues and ornaments would be suitable? From the 1920s onwards Jos Schmutzer would become actively involved in the development of a so-called Javanese-Christian visual language. One of the underlying concerns was to familiarise newly converted Javanese with Catholic dogmas by presenting Catholic themes and its pictorial traditions in local styles. Java’s Buddhist and Hindu past, despite having been largely replaced by Islam for most the 20th-century was favoured in order to attain this goal. The search for a Javanese-Christian imagery such as realised in the Sacred Heart statue (fig. 2), the Holy Trinity (fig. 3) and the Blessed Virgin Mary (fig. 4) today raises deeper questions concerning how the visual language came about, who were the actors involved and how its development was received.

Predictably, the development demanded collaboration. It marks a multi-layered story of cultural exchange and co-creation within the Dutch-East Indies colonial context. This collaboration – a term which of course also triggers tension – was propelled by Iko, a sculptor of Sundanese decent from Cimahi. Cimahi was then a small town in western Java just outside Bandung, which has since sprawled into it. In Iko, Jos Schmutzer saw a suitable craftsman to help shape his ideas and turn them into real objects.[1] Introducing Iko only through the lens of Jos Schmutzer may not be entirely justified however. Iko was more than an extension of Jos Schmutzer’s ideas or the recipient of one-directional commissions. Their collaboration was much more complex than the clear separation between artist and producer – a separation which ultimately further perpetuates the telling of histories within colonial points of view.

It is believed that Iko was an autodidact in West Java, which is traditionally less known for the production of naturalistic carvings.Before his acquaintance with Schmutzer, Iko already had local popularity and significant commissions to his name. Before his fame, according to Wassing-Visser, Iko would also have initially devoted himself to carving wajang golek dolls and figurative figurines of dancers, the so-called bedayas and serimpis (fig. 5)[2]The earliest work that can be attributed to Iko concerns a carved bust of Queen Wilhelmina (fig. 6), which was made in the likeness of a photograph showing a bronze bust of the monarch. The then regent of Bandung, Raden Adipati Aria Martanagara, commissioned Iko to create this sculpture in 1898. Around 1900, Iko also made significant contributions to the Indische Zaal. Schmutzer would not refer to these projects often.

Nevertheless, Jos Schmutzer did often express his admiration for Iko, such as by noting that ‘a treatise on Iko’s oeuvre could take form as an extensive book section’. Since then, a comprehensive study has still not appeared however. As a non-upper class Javanese, Iko’s birth date and death date remain unknown. Just like his oeuvre, knowledge concerning the talented Javanese Sundanese carver is scattered, fragmented across short 1920s newspaper articles and magazines or personal archives. Photos and examples of his works cannot fill in the past like a gap, but they nevertheless do offer ways in which to tell a rich story. From Bedaja to Madonna: the Javanese sculptor Iko, which grew into a book rather than the proposed book section makes a first important step in telling Iko’s story in terms of a cohesive oeuvre and a thought-provoking example of shared Javanese-Christian heritage. The first chapter recounts how Iko became a well-known artist in Java during the beginning of the 20th century. This happened via commissions for sculptures, gifts for dignitaries and portraits of well-to-do people. The second chapter discusses the art for the mission, specifically in what ways Iko collaborated with Jos Schmutzer. Most of these were djati wood sculptures and have been on loan from the Schmutzer family since 1987 as the Schmutzer Collection at the Steyl Mission Museum.[3] The third chapter takes the question of collaboration more seriously, introducing the concept of ‘hybridity’ in contemporary terms of shared authorship and heritage.

1. Acquainting Iko

In his first and most difficult years as a sculptor, Iko was taken under the wing of the education inspector C. den Hamer. In the early twentieth century, Den Hamer was inspector of inland education for the Department of Education, Honour and Industry in the Dutch East Indies. In this function he was liaison with the local industry committees for which he often travelled across Java. He thus most likely had a good indicator of quality in terms of Javanese arts and crafts.[4] Den Hamer is said to have ‘discovered’ Iko by chance, and even though the very first works created under his guidance were not yet of exceptional quality, Den Hamer nevertheless immediately recognised Iko’s talent for sculpture.[5]

The artistic and commercial importance of ‘indigenous handicrafts’ was emphasised not only in the Dutch East Indies but also in the Netherlands. By 1900, regular exhibitions showing handicrafts were already being organised. In 1899, on the initiative of Geertruida van Zuylen-Tromp and her husband Gustaaf E.V.L. Van Zuylen, among others, the Vereeniging Oost en West was founded in The Hague. The association also wanted to make the products of Dutch-Indies arts and crafts known to a wider public, connecting them to the Dutch market. Boeatan, a shop in the Hague was an example of this. Concerns with an emphasis on the quality of the arts and crafts quickly emerged as a result of this new trade. In the popular press of 1906, educator Th. J.A. Hilgers stressed the importance of expert guidance from ‘native’ artists and warned against the emphasis on quantity. According to Hilgers, the association Oost en West encouraged too many mediocre ‘native’ artists to produce as much as possible. Subsequently, in Hilgers’ point of view, the art-loving Den Hamer was exactly who he was looking for to stimulate indigenous arts and crafts in a more favourable way. The relationship with Den Hamer must have been crucial for Iko. Den Hamer initially supported him through simple assignments and quickly realised Iko’s exceptional talent.

The Indische zaal is an early example of Iko’s contribution. The room in the Noordeinde Palace in the Hague was made on behalf of the people of the Dutch East Indies as a wedding gift to Queen Wilhelmina who married Prince Hendrik, Count of Mecklenburg (fig. 7) in 1901. For this room, Iko made two copies of Javanese temple statues. He received this commission through Den Hamer who also closely supervised the creation of the sculptures. The first sculpture concerned a Shiva as Mahadena executed in trachite, a volcanic stone commonly found in Java. It was a copy of an original from Semarang that was in Batavia at the time, albeit in damaged condition.[6] Iko first made the sculpture out of djati wood. While working however, the wood began to show cracks, presumably caused by the fragile material not drying properly.[7] In volume eight of Techniek en orerkunst in den Indischen archipelago, Loebér referred to this problem too, yet from a different perspective. According to Loebér, it testifies to the ‘nonchalance’ the native artist still has towards his material.[8] According to Rita Wassing-Visser’s more investigative research and critique, it was actually Iko himself who decides to continue working in trachyte, a type of stone. The original statues that served as models for the ones that Iko carved for the Indische zaal are today considered among the most skilled examples of Java’s Buddhist-Hindu past in the early twentieth century.[9] A picture of Iko working on his copy of the bodhisattva Manjusri would be later presented by Abendanon to Queen Wilhelmina in 1906 during the official presentation of the Indische zaal.[10]

Apart from a small sculpture from 1914, not much is known about Iko’s work during the 1910s. He would no longer use stone from this point on. According to some sources, this may have been due to the suffering from an eye disease which nearly blinded him. Recovery would have taken place by the time he came into contact with Jos Schmutzer however. In any case, in 1918 Iko came into contact with H. van Meurs, the later deputy secretary of the Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen (Royal Tropical Institute). Van Meurs would also play an important role in Iko’s work for the Catholic mission. A vivid 1941 article written by him as he reflects on the past, elaborates on multiple key moments. The bond between Van Meurs and Iko grew shortly after World War I. At the time, French prime minister Georges Clemenceau (fig. 8) was touring Java. In response, the local authorities were prompted to consider a suitable gift. Iko was selected to carve two Javanese-Hindu court dancers out of djati wood, so-called bedayas, which were presented to Clemenceau in Bandung (cat. 13-14). It was through these works that Van Meurs came in contact with Iko. Soon after, Van Meurs attempted to relieve him from any ‘commercial’ work by providing Iko with more permanent assignments, as he too believed this would lead to better quality.

Yetdespite the efforts to stay away from ‘commercial’ work, it was precisely the ‘commercial’ work that would contribute to Iko’s reputation. Van Meurs began to see opportunities especially in missionary art commissions, noticing that they could offer stability for Iko. Van Meurs took it upon himself to establish a small art committee focussed on how Iko’s style could be gradually adapted to the requirements of missionary art.[11] This committee included the parish priest Sterneberg and Monsignor Van Velzen, who was still parish priest at Buitenzorg at the time. By this time, Jos Schmutzer had also been approached to inform him of the committee’s plans. The committee occupied Iko with a number of assignments. In order to familiarise himself with the theme of the Virgin with the baby Jesus, Iko first cut an image from a more general depiction of a Sundanese mother with child (cat. 29).[12] According to Van Meurs, the pastor was not yet convinced by suggesting that the rendition lacked tenderness, particularly in the mother-to-child smile.[13] Jos Schmutzer however praised Iko’s bedaja in which his talent was supposedly expressed at its best. It was here that Schmutzer saw reason to realise his ideal of a Hindu Javanese-Christian art with Iko.[14]

2. Art for the mission: the Iko-Schmutzer sculptures

On their plantation and sugar factory at Ganjuran, Jos and Julius Schmutzer and their wives established several schools, an orphanage and a hospital for the local population.[15] Right next to the enterprise, passed down in the family in 1912, a church and the Sacred Heart Chapel were erected, the latter of which was built in the form of a Javanese-Hindu temple, a Candi. The foundation stone for the Sacred Heart Chapel at Gondang Lipoero was laid by Van Velzen himself on Christmas Day in 1927.[16] This would be one of the main locations for Schmutzer’s collaboration with Iko. A stone version of a Sacred Heart statue designed by Jos Schmutzer and previously carved from djati wood by Iko was placed in the chapel in early 1930. The church building would also contain several stone statues resulting from the joint work of Schmutzer and Iko including yet another copy of a stone Sacred Heart statue.[17] Sadly, the church building at Ganjuran as conceived by Jos Schmutzer no longer exists. On 27 May 2006, it largely collapsed as a result of the powerful earthquake near Yogyakarta. The church was rebuilt in 2009, but no longer to the original design (fig. 9).[18] In the current church, which has the shape of a traditional Javanese pendopo, one can still see the altar with two stone versions of praying angels. The same applies to a fourth statue in the church, that of a seated Madonna with Christ Child on her lap. While this statue is particularly reminiscent of an Iko statue, it was made by another Javanese sculptor at the request of the locals after the war.[19]

Holy Trinity and Christ representations

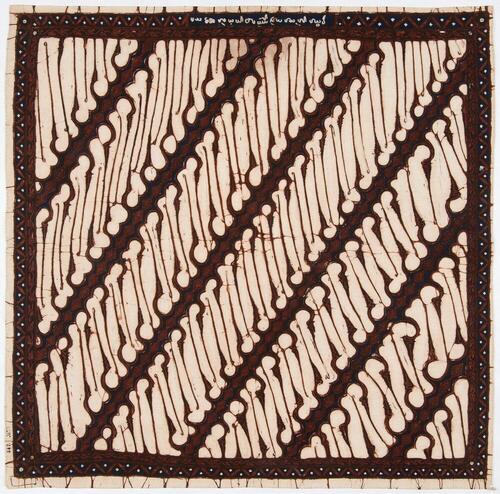

When it comes to the important Catholic themes in art, the Holy Trinity arguably presented Jos Schmutzer and Iko with the greatest artistic and didactic challenges. According to Schmutzer, the emphasis of the Holy Trinity was on the idea of divine love. Iko spent three months working on its execution in djati wood. The seat of this Holy Trinity reminded Schmutzer of the Maitreya seat of Candi Plaosan, a Buddhist temple north of Yogyakarta, not far from Prambanan.[20] Schmutzer’s family archive contains a sketch showing a number of floral and flame motifs borrowed from Plaosan, which he selected specifically for the Holy Trinity statue (fig 10). It consists of three personifications, as is traditionally always the case. From left to right (from the viewing perspective) feature the Son holding the attribute of the cross (fig. 11), the Holy Spirit holding a dove (fig. 12), and the Father holding a crown as his attribute (fig. 13). Clothes and crowns were originally Hindu, according to Schmutzer however, Iko made small adaptations. The crowns for example were slightly modified to make them appear more graceful in shape. On the garment, the batik-derived parang roesaq motif can be recognized (figs. 14).[21] On the upper body, the figures wear a traditional shoulder cloth, the slendang, which is worn by gods, hermits and teachers in traditional wajang performance. According to Jos Schmutzer, the attire supposedly emphasises the role of God as a teacher who makes himself known through the Holy Trinity.

The mission also operated in an Islamic context in Java. This may explain why Schmutzer also tasked Iko to carve another Holy Trinity with a singular personification – the Son – featured, instead of three personifications. Iko executed this version in the same regal style as in the earlier Holy Trinity. With one hand the Son makes the gesture of blessing while holding a globe with the other. In its current display at the Steyl Mission Museum, the statue stands on a large wooden cabinet and is accompanied by two praying angels. The robes and attributes of the praying angels symbolise those of the Javanese aristocracy and also their modest, serving and thankful attitude expressed in the hands – as one would approach a sultan.[22] Additionally, unlike the European tradition of standing or kneeling angels, the Javanese angels are depicted as sitting in the lotus position. According to Eastern tradition, this expresses dignity and modesty. In this particular case, it communicates the angels’ service to God.[23] Subsequently, local codes play a large role.

Javanese Madonnas

The worship of the Virgin Mary, integral to Catholicism is also a major theme for the Schmutzer-Iko collaboration. This had to be done with caution however. As with the Holy Trinity, the portrayal and representation of Mary in isolation could also lead to confusion. Understandably, the appearance of Mary as a stand-alone goddess would be unfavourable for the central understanding that there was one God. Mary was thus always portrayed in relation to the Christ Child. The Steyl Mission Museum has an example of a enthroned Madonna dressed in a sarong on display, a theme known in European art history as the Maestá. In this rendition, the Christ Child sits on her lap (fig. 15). A third variation on the theme concerns a standing Madonna carrying the Christ Child in her right arm. According to Jos Schmutzer, the first two Madonnas were inspired by Hindu-Javanese images, those of Candi Plaosan and Candi Singosari.[24] Within the missionary context however, tensions began to grow in to what extend symbols such as the Buddhist lotus flower should be used. One of the critics included the German theologian Aufhauser who claimed that ‘ghosts of the past’ should be avoided, for yet again, the perceived risk of confusion.[25]

In Europe, the tradition developed over the centuries from an archetypal mother-child representation to that of Mary as the intercessor of humanity and the bringer of divine grace.[26] However short the tradition of the Javanese Madonnas was in 1935, Jos Schmutzer noted a similarity with the development of Marian depictions in European art history in terms of an increasing ‘realism’. Schmutzer’s conceptualization of realism most likely did not refer to the naturalistic aspect of a representation, or degree of resemblance however. Rather it more likely referred to the degree a representation connects to everyday life. This compares, for example, to how in the late European Middle Ages Christian art increasingly conformed to the believer’s concrete environment in terms of its repertoire, for example as through the presence of a Flemish landscape.[27] Schmutzer identified a problem in how the development in Javanese-Christian art could compare and that it must subsequently also be judged differently. He argued that the educational focus of the art cannot be left out of consideration. This function meant that the missionary art deviated from formal and symbolic rules for an educational reason in specific: to ensure successful conversion. Most of the formal rules, such as particularities in attire, posture, hairstyle and facial hair may have endured in Europe, but did not in Java specifically due to this missionary context.

The Stations of the Cross

Another way of offering clear and culturally accessible communication of the new Catholic doctrines was through the Stations of the Cross – a ‘colour book’ or a series of representations showing Christ’s crucifixion. A Stations of the Cross was also part of Jos Schmutzer’s plans for Ganjuran, yet it would never be completed. Apart from the frames, Iko only cut two of the fourteen intended representations, which today reside in the Steyl Mission Museum.[28] In 1947 however, Lucie Schmutzer-Hendriksz commissioned the completion of the Stations of the Cross after all, and she approached the Java-born architect Henri Maclaine Pont to do so.[29] He was by then an acquaintance of the Schmutzer family. Maclaine Pont was familiar with the site, having reconverted to Catholicism himself there in 1931 at the Sacred Heart Church in Ganjuran. He completed sketches for 14 stations.[30] His approach differed from Iko’s original plans, perhaps suggesting criticism. While he was positive about the humanity of Iko’s Christ figure, he was fundamentally critical of the depiction of the Scribe, which he argued exalted more dignity than Christ.[31] This criticism may not so much be a criticism of Iko’s artistry however. Rather, it can also be read as a form of admiration for Iko’s artistry, as he had the capacity to depict deeper levels of expression. Either way, Maclaine Pont, like Iko would never complete the project either. What can instead be seen in Ganjuran today are much less refined executions inspired by Jos Schmutzer and Iko’s designs executed at a later stage.

Wandering works

Thanks to Jos Schmutzer’s writings and press coverage of the missionary art, much is known about Iko’s contribution in this period. It makes it possible to reconstruct this part of his oeuvre. When it comes to his other works which fall outside of this category however, it proves much more difficult. Judging from what Van Meurs wrote in 1941, Iko made more than a hundred figurines in the period before he started working for Schmutzer alone. Many of these were sold door-to-door, by the hotel association, and even by Van Meurs himself. As a consequence, many of his works and their stories are untraceable. One notable event stands out during this period however. In 1930, an exhibition of Iko’s work takes place at Boeatan on Heulstraat in The Hague. This is reported by the Colonial Weekly on 2 October 1930 and multiple other outlets. According to a report from the Haagsche Courant of 26 August 1930, the exhibition included “wayang-wong dancers, Serimpis, Buddhas, Ganeças, etc”.[32] On the same day, The Koerier and the Maasbode report that about a dozen statues were involved.[33] On 25 August 1930, even a lecture takes place during which J.A. van Dijk from Soekaboemi shares his admiration with an interested audience.[34] The Colonial Weekly also describes how Iko was no longer the youngest during this time. It is unknown when he died, but according to this observation it is likely that it was somewhere in the 1930s, perhaps early 1940s.

3. A shared cultural heritage

Although the reconstruction of Iko’s oeuvre remains incomplete, it does become evident that it is both an Indonesian and Dutch art history. Whether they are sculptures for the Indische zaal, works for the mission, sculptures made for private individuals, or objects sold door-to-door, they are difficult to define as ‘autonomous’ works of art; at least, within a ‘Western’ European framework. Similarly, Iko’s oeuvre would be short-changed if considered purely a consequence of commission. As mentioned prior, who were defined as actors at the time may have largely been shaped by the colonial situation and power relations at the time. The question is whether there was a business agreement with Iko and what it looked like. In any case, the brothers Jos and Julius Schmutzer were committed to the Javanese working for them. This can also be deduced from the collective bargaining agreement relatively favourable to the workers at Gondang Lipoero. Questions concerning authorship and ownership quickly become complex too however. Exactly how ownership of the sculptures came about is not entirely clear. The scattering of sculptures across Dutch public collections also makes them part of what can be considered a collective postcolonial context. Subsequently, this context can perhaps best be considered part of an ongoing endurance of the past and a changing relationship between Indonesia and the Netherlands.

Attribution and ownership / acclaim and criticism

Although Jos Schmutzer’s ideas were leading in creating a Javanese-Christian style, it is undeniable that the sculptures owe their stylistic quality largely to Iko’s sculptural skill. Schmutzer was partly responsible for the development of the style when it comes to the choice of certain ornaments and symbols to recur in it, as he was the one who brought the Catholic inspirations. The design sketches and drawings preserved in the family archive in Nijmegen testify to this. These drawings may have served as instructions for Iko, as details include data on the planned size but also on the proportions into which the intended wooden sculptures should be carved. Somewhat funnily, Jos Schmutzer was by no means a gifted draughtsman. Perhaps as a result, Iko’s images still sometimes lack the right proportions. Recognising these shortcomings, Schmutzer wrote the following to his sister in 1925 that it is his own ‘clumsy drawings’ in which he himself can be recognised.[35] For the moment, the conclusion can be drawn that Iko and Schmutzer overcame the shortcomings together. In the exhibition Our Lady in the Art of the Missionary Countries in the hall of Westminster Cathedral in London in 1939, the accompanying labels read ‘Schmutzer-Iko’. Interestingly, the Steyl Mission Museum today identifies the sculptures as conceived by Schmutzer and made by Iko. The character of their collaboration is thus still documented in varied ways.

Jos Schmutzer was fearful of critique or the misunderstanding of the project, specifically from the perspective of modern artists. For this reason, most sculptures remained in private spheres. Criticism eventually came however, yet from a different angle. In the 1920s, the response to Indonesian nationalism in Java was a general form of cultural restraint. It increased the awareness within missionaries of the danger of excessive ‘Europeanism’ in order to avoid enflaming antagonism.[36] In Europeanism or Catholicism authors Jos Schmutzer, Jesuit J.J Ten Berge and architect Willem Maas define ‘Europeanism’ as the tendency to see European culture and its art as superior to that of the mission’s country and to impose it on its inhabitants. The mission rejected that this was the case for Catholicism. The argument quickly became that Catholicism was a universal faith and thus able to be separated from Europeanism. Additionally, Ten Berge’s contribution reveals that he actually also considered European styles inappropriate for the Javanese mission for several reasons. According to Ten Berge, the Javanese pagan soul was not a blank canvas, but was instead already embedded in a long existing tradition of painting, sculpture, music, theatre, dance and architecture.[37] Moreover, in the art of Java he saw ‘beauty’ and ‘elevation of form’, and therefore no reason to want to replace it for an art style based on European forms – or Europeanism.[38] The arguments in Europeanism or Catholicism concern what was most favourable for missionary work however. It can be considered as missing the mark in what was really the matter of concern: the imposition of cultural hierarchy, whether European or Catholic.

Colonial spirits were also expressed in other convictions, such as that the Javanese and their art carry various sorts of limitations and incapacities. Stereotyping was not uncommon in colonial literature and commentary on the ‘native’ population of the Dutch East Indies. To begin with the early sources, the success of the new visual style was for example evaluated by the extent to which it was adapted to what was seen as the Javanese people’s vernacular and, in a broader perception, the so-called ‘Asian psyché’. This point of view was supposedly more attuned to the mystical and the emotional, while it rated the purely spiritual, the intellectual and the rational less highly.[39] In 1935, Richard Baumgartner, in a Vienna lecture, argued that this supposed Javanese sensitivity to the mystical was the reason why the Catholic mission in Java could be fairly successful. Indeed, even in the Catholic faith, the emphasis was more on the mystical and on the many ceremonies and other external aspects through which the population can be reached.[40] According to Baumgartner, with regard to this more mystical and emotional attitude, Javanese, for example, could not be expected to be very active and persistent in scientific activities however. In his view, the Javanese’s nature was instead dreamy and contemplative.[41]

Such views provided a breeding ground for paternalistic attitudes, which paradoxically consisted of a deep respect for what is seen as the indigenous culture on the one hand, but on the other hand presented Europeans as the guardians of that culture and as bringers of new forms of civilisation.[42] Paternalistic attitudes can also be found in between the lines of mission texts at Ganjuran. Maclaine Pont, as discussed earlier writes with admiration and inspiration about Javanese culture, but also identifies himself as the person who can connect the Javanese with what is perceived as their cultural heritage – mostly the Buddhist-Hindu heritage, Islamic heritage is often left out.[43]

A belief in essentialisms also characterised this response to the new Javanese-Christian art. Van Meurs describes how Christian and Hindu ideas are characterised by the transcendental, but that Javanese-Hindustani art is essentially more formal and emotionless. Christian art on the other hand was supposedly emotionally involved in a more intimate and positive way. It is interesting that he still believed in supporting an artform which combined the two supposedly unbribable characteristics.[44] Additionally, there is also criticism from the Javanese Catholic Prawirapratama. This appears in two parts in de Maasbode of 20 and 21 October 1927. According to Prawirapratama, the very idea behind the Iko statues of adhering as much as possible to local still-living traditions is not fulfilled. The so-called ‘traditional’ Buddhist-Hindu style is according to him incompatible. Prawirapratama claimed that Iko’s soul is essentially Sundanese instead of Javanese, which in his view caused the problem of Sundanese features being ‘mixed up’ with Javanese ones, such as in the patterns of the robes.[45]

Returning to Ganjuran

Despite the criticism of the Iko-Schmutzer project as early as the 1920s and 1930s, critical thinking on issues of cultural influence, appropriation and exchange characteristic of the colonial context only really took off after the colonial era. It provokes the question of how the Iko-Schmutzer sculptures can be interpreted again today. Are the sculptures examples of a hybrid art form that manages to mediate between different cultural identities or are they, less positively interpreted, a ‘bastardization’ or even a form of cultural appropriation?[46] This of course depends very much on whom speaks and from which perspective the question is asked. In a sense, Prawirapratama’s critique partially anticipated contemporary debates on ‘cultural hybridity’, a concept within postcolonial discourse.

According to contemporary Indian philosopher Homi K. Bhabha, cultural hybridity stands for a process that allows people to move back and forth between more or less fixed identities, without being permanently confined to one of them. This movement subsequently allows people to see differences and embrace similarities without falling into hierarchies. To explain how this works, Bhabha uses the spatial metaphor of the staircase. In this staircase it is the in-between space which is important, or, in other words, the space in which the moving back and forth takes place.[47] Within this philosophy, a cultural object can become an ‘agent’, challenging one to take a step up the metaphorical ladder that moves between identities. Seen this way, the Iko-Schmutzer works can also be positioned on the metaphorical staircase, moving somewhere back and forth between Christian identity, between what was perceived as Javanese identity at the time, and between how that identity was actually experienced. Iko’s identity as also a Muslim would have given him an even broader dimension. The metaphor literally echoes the staircase of the Sacred Heart Chapel at Ganjuran.

In the last decades of the century, hybrid cultural art forms, in the broadest sense of the word, emerged almost automatically within what in Western Europe and North America was called the multi-ethnic or multicultural society. In such a multicultural society, people from different cultural backgrounds increasingly interact with each other in public and cultural life such as in music studios, at art academies, theatres, clubs and on the streets. This post-war, predominantly North American and European cultural context cannot simply be projected onto that of Java in the 1920s however. Even though the Javanese society of the time was to some extent multicultural, the political and cultural conditions of the society in which Iko-Schmutzer worked, was largely defined by the enforced separation of ethnic and cultural groups. In the 1920s, this society still suffered from colonialism. Within it, the Dutch, who held a large amount of power, including other Europeans, made up only 0.4 per cent of the population.[48] Subsequently, the presence of cultural diversity may say little about power relations and cultural dominance. As such, Iko’s oeuvre encourages us to keep thinking about how both countries developed culturally after independence but also how the still relate to one another; from Ganjuran to Steyl, from Bedaja to Madonna, and vice versa. For further elaboration on how Iko and his work continues to question and entangle histories for contemporary audiences today, see From Bedaja to Madonna: the Javanese sculptor Iko.

Summary and translation, Margot Stoppels.

[1] Iko was a Muslim and, as far as is known, never converted to Catholicism.

[2] Wassing-Visser, 142-144. Wassing-Visser does not name the source of this information in her book but it is probably Noto Soeroto’s article in the magazine on the Dutch East Indies House. According to Noto Soeroto, the difficult commission Iko commenced had been given to him by Den Hamer. He also describes that the second sculpture was carved in the likeness of one that was once in the museum of the Bataviaasch Genootschap but ended up in Berlin at some point. Subsequently, Noto Soeroto is talking here about the Manjusri statue, but even though the anecdote about the problems with the wood in this 1913 article seems to be the same as that described by Wassing-Visser, Noto Soeroto did not discuss it at the time in the context of the Indische zaal, about which he writes next to nothing, despite later devoting an entire publication to the same Indische zaal. Neverthless, Noto Soeroto does describe the same photograph as Wassing-Visser and it is also printed in his article. Noto Soeroto also describes that the photograph was given to Queen Wilhelmina by J.H. Abendanon. See Noto Soeroto, ‘Iko,’ 153-154. Den Hamer was also involved in research on Hindu-Javanese architecture as we can read in Professor Kern’s ‘Preliminary Report’ in the 1904 Tjandi Djago report of the Commission for Archaeological Research on Java and Madura (the forerunner of the later Archaeological Survey). See Kern, ‘Preliminary Report’, X.

[3] MS. Letter from curator Truus Coppens to Gregorius Utomo, Steyl 18-06-1997.

[4] Abendanon, Rapport van den directeur van Onderwijs, Eeredienst en Nijverheid, 128-129.

[5] Hilgers, ‘An Inlandsche Artist’, 664.

[6] Noto Sueroto, ‘Iko,’ 155. However, Wassing-Visser writes in 1995 that the original sculpture is said to be in the Shiva temple of the Candi Loro Jonggrang at Prambanan. See Wassing-Visser, Royal Gifts, 243 note 21.

[7] Wassing-Visser, 144.

[8] Loebér, Wood carving and metalwork in the Netherlands East Indies, 8.

[9] Wassing-Visser, 142-144.

[10] Wassing-Visser, Royal Gifts, 142-144.

[11] Meurs, ‘Iko, the Sundanese sculptor,’ 105.

[12] Meurs, ‘Iko, the Sundanese carver,’ 105.

[13] Meurs, ‘The preaching of the Christian doctrine of salvation,’ 105.

[14] Schmutzer, ‘Christian-Javanese art,’ 68-69.

[15] Steenbrink & Aritonang, A history of Christianity in Indonesia, 702-703. Steenbrink and Aritonang refer to the plantation as Tjipto Oetomo in their article. However, this was the name of the union with which the plantation reached a rather unique collective bargaining agreement in 1918. For this, see MS, Collective bargaining agreement concluded tusschen onderneming Gondang Lipoero and the Vereeniging Tjipto Oetomo in 1918. See also Santosa, ‘Transformation of the Ganjuran Church Complex.’ 44.

[16] KDC, SCHM 126, 32. Note by Dr J. Schmutzer, ‘On Christmas Day of the Year O.H. 1927 (…).’

[17] Schmutzer, ‘Christian-Javanese Art,’ 80. A design for this church is also printed in this publication. See pages 82-84. See further Steenbrink & Aritonang, A history of christianity in Indonesia, 929. It is noted that the chapel is said to have been designed in the likeness of one of the temples from the Prambanan temple complex that is said to be dedicated to Shiva. In keeping with a Hindu tradition, a blessed version of the Sacred Heart statue was bricked into the base of the temple.

[18] Santosa, ‘Transformation of the Ganjuran complex,’ 46.

[19] KDC, SCHM 126, 88.

[20] Schmutzer, ‘Christian-Javanese art,’ 71.

[21] Fraser-Lu, Indonesian Batik, 37-39.

[22] Schmutzer, 77 – 78.

[23] Vroklage, ‘Inlandsche art and Christianity in the N.-O.-Indies,’ 54.

[24] Schmutzer, ‘Javanese Madonnas,’ 216.

[25] Aufhauser, ‘Christliche einheimische Kunst in Nichtchristlichen Ländern,’ 168.

[26] Schmutzer, ‘Javanese Madonnas,’ 220-222.

[27] See also Constantini, ‘Il problema dell’arte missionaria,’ 58.

[28] Its ornaments were designed after examples of ornaments on temples such as those at Candi Rimbi.

[29] MS. Letter from Ir. H. Maclaine Pont to Mrs Schmutzer, Groede 22-11-1947.

[30] Vries & Segaar-Höweler, Henri Maclaine Pont, 54.

[31] CNI, MACL 39, ‘Notes on draft sketch designs,’ 3-5.

[32] ‘Boeatan.’

[33] ‘The Sundanese sculptor Iko.’ The Courier; ‘The Sundanese sculptor Iko,’ The Maasbode.

[34] ‘Boeatan.’

[35] Private collection Schmutzer. Letter from Jos Schmutzer to his sister Elise Anna Maria Antonia (Lili) Schmutzer, Buitenzorg, 9-11-1925.

[36] Aufhauser, 163.

[37] Berge, ‘Christian indigenous art in the mission,’ 11.

[38] Berge, 14.

[39] Aufhauser, ‘Christliche einheimische Kunst in Nichtchristlichen Ländern,’ 172.

[40] KDC, SCHM 126, 32. Baumgartner, ‘Hindu-Javanische Kunst im Dienste der Kath.Kirche,’ lecture by Ing. Richard Baumgartner delivered before the Austrian-Dutch Association, Vienna, 1935.

[41] Baumgartner, ‘Batavia,’ 27.

[42] In 1938, journalist Willem Walraven described the ‘natives’ as ‘extraordinarily careless and destructive’. It was said to be thanks to the Dutch that something of the Javanese past had been preserved because if it had been up to them they would have already ‘probably sold everything to the highest bidder’. See Walraven, Letters, 247.

[43] Vries & Segaar-Höwelaar, Henri Maclaine Pont, 35; Van Leerdam, Architect Henri Maclaine Pont, 152.

[44] Meurs, ‘Iko, the Sundasche sculptor,’ 106.

[45] Prawirapratama, ‘Christian-Javanese Art II.’

[46] Abendanon, Rapport van den directeur van Onderwijs, Eeredienst en Nijverheid, 3-4.

[47] Bhabha, The location of Culture, 3-4.

[48] Reybrouck, Revolusi, 80.

(1), (detail zoon + kruis) 1924-1925, djatihout, 115 x 105 x 47 cm., Missiemuseum, Steyl, objectnummer Schm01.

(1), (detail heilige geest + duif) 1924-1925, djatihout, 115 x 105 x 47 cm., Missiemuseum, Steyl, objectnummer Schm01.

(1), (detail vader + kroon) 1924-1925, djatihout, 115 x 105 x 47 cm., Missiemuseum, Steyl, objectnummer Schm01.